This article delves into the intriguing origins of windshield wipers, tracing their evolution and examining their profound impact on automotive safety and convenience. From their inception to modern advancements, the journey of windshield wipers is a testament to human ingenuity and the relentless pursuit of improved driving experiences.

The history of windshield wipers can be traced back to the early 20th century, a period marked by significant innovation in automotive design. The initial concept emerged as a response to the need for enhanced visibility during adverse weather conditions. In 1903, Mary Anderson patented the first functional windshield wiper, a groundbreaking invention that would pave the way for future developments.

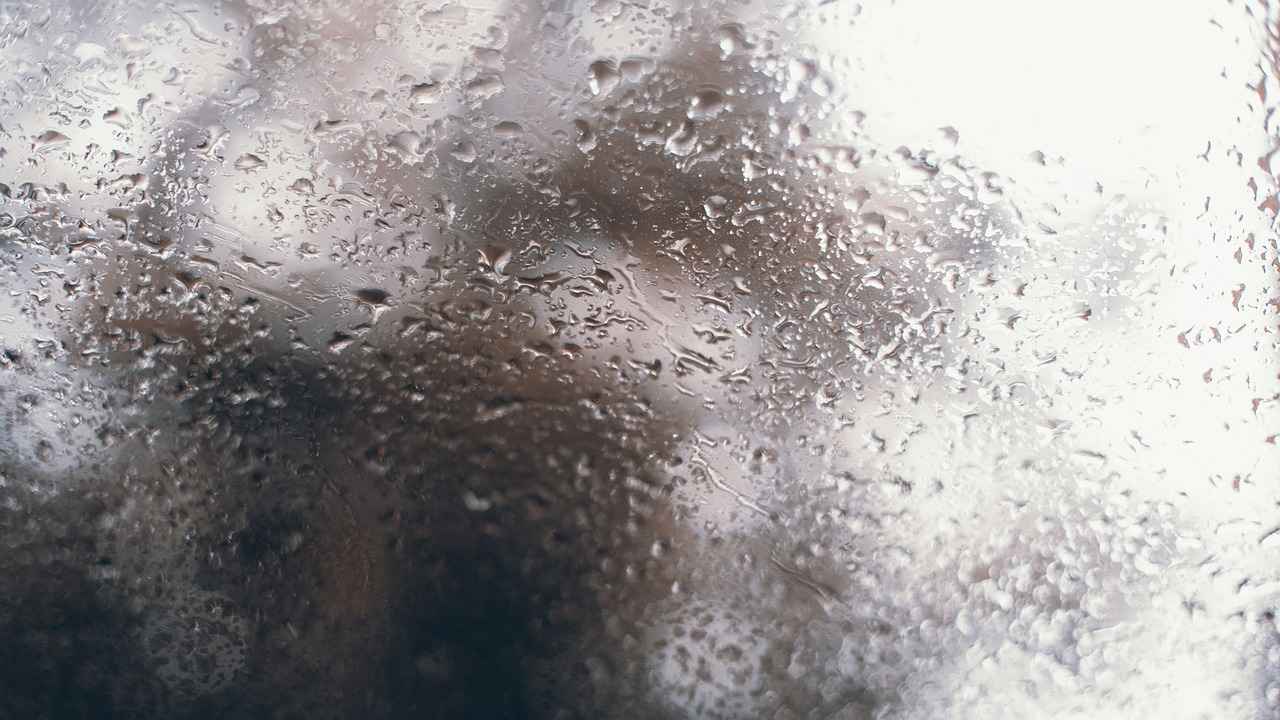

Early windshield wipers were manually operated, requiring the driver to intervene to clear the windshield. This section explores the mechanics of these initial designs, which often featured a simple arm and blade mechanism. The challenges faced by early automobile manufacturers were significant, as ensuring driver visibility during heavy rain was a critical concern.

The transition from manual to automatic windshield wipers marked a pivotal advancement in automotive technology. This shift not only enhanced convenience for drivers but also significantly improved overall safety. Automatic wipers, which began to emerge in the 1920s, allowed for continuous operation without driver intervention, making them essential for safe driving in changing weather conditions.

Over the decades, windshield wiper technology has continued to evolve. Key innovations include:

- Intermittent Wipers: Introduced in the 1960s, allowing drivers to control the frequency of wiper movement.

- Rain Sensors: Automated systems that detect moisture on the windshield and adjust wiper speed accordingly.

- Heated Wipers: Designed to prevent ice and snow buildup, enhancing visibility in winter conditions.

Each advancement has contributed to the reliability and performance of modern windshield wipers, ensuring that they meet the demands of today’s drivers.

Several inventors played crucial roles in the development of windshield wipers. While Mary Anderson is often credited with the initial invention, her work inspired a wave of innovation. Other notable figures include:

- William M. McKinley: Improved upon Anderson’s design in the 1920s, leading to more effective and efficient wiper systems.

- John H. W. McNaughton: Developed the first electric windshield wipers, revolutionizing how wipers functioned and enhancing driver convenience.

These pioneers collectively advanced the technology, ensuring that windshield wipers became a standard feature in vehicles, ultimately enhancing automotive safety.

The impact of windshield wipers on automotive safety cannot be overstated. By significantly improving visibility during rain, snow, and other adverse weather conditions, windshield wipers have played a crucial role in reducing accidents. Their evolution from manual to automatic systems has not only enhanced driver convenience but also contributed to safer roadways.

In conclusion, the fascinating history of windshield wipers reflects a broader narrative of innovation within the automotive industry. From their humble beginnings to the sophisticated technologies of today, windshield wipers remain an essential component of vehicle safety, showcasing the importance of continuous improvement in automotive design.

What Are the Origins of Windshield Wipers?

The fascinating journey of windshield wipers unveils a remarkable narrative of innovation and necessity in the automotive industry. Understanding what led to their invention and how they have evolved over time provides valuable insights into the importance of vehicle safety and driver convenience.

The origins of windshield wipers can be traced back to the early 1900s, a period marked by rapid advancements in automotive technology. The first functional windshield wiper was invented by Mary Anderson in 1903. Her design featured a manual lever that operated a blade to clear rain and debris from the windshield. While her invention was not commercially successful at the time, it laid the groundwork for future developments.

In the early days, vehicles lacked the sophisticated designs we see today, and visibility during inclement weather was a significant concern. The initial designs were rudimentary, consisting of a simple arm and rubber blade mechanism. This meant that drivers had to actively operate the wipers, which was cumbersome and often ineffective during heavy rain.

Early windshield wipers were entirely manual, requiring drivers to pull a lever to activate the wiping mechanism. This design posed several challenges, particularly during adverse weather conditions. Drivers often found it difficult to maintain visibility while also controlling the vehicle, leading to safety concerns.

As automobile manufacturers recognized these issues, they began to explore more efficient solutions. The need for improved visibility prompted the transition from manual to automatic systems, a significant milestone in automotive technology.

The introduction of electric windshield wipers in the 1920s marked a revolutionary change in the automotive industry. This innovation allowed for automatic operation, significantly enhancing driver visibility during rain or snow. The electric wipers utilized a motor to control the movement of the blade, making them more efficient and reliable than their manual predecessors.

Over the decades, windshield wiper technology has continued to evolve. Modern wipers now feature advanced systems such as variable speed settings, rain sensors, and even heated blades to prevent ice buildup. These innovations have drastically improved performance and reliability, ensuring that drivers maintain clear visibility under various weather conditions.

While Mary Anderson is often credited with the invention of the first windshield wiper, several other inventors played a crucial role in refining this technology. Notable figures include John A. McCulloch, who developed the first electric windshield wiper system in 1921, and Charles H. H. Smith, who patented a more efficient design in the late 1920s.

These pioneers collectively contributed to advancements that have shaped the modern windshield wiper systems we rely on today. Their efforts not only improved the functionality of wipers but also significantly enhanced overall automotive safety.

In summary, the history of windshield wipers is a testament to human ingenuity and the ongoing quest for safer driving experiences. From manual designs to sophisticated automatic systems, the evolution of windshield wipers reflects the broader trends in automotive innovation, emphasizing the importance of visibility and safety for drivers everywhere.

How Did the First Windshield Wipers Work?

Windshield wipers are essential components of modern vehicles, ensuring clear visibility during rain and adverse weather conditions. However, their journey from rudimentary designs to sophisticated technology is a fascinating tale of innovation and necessity. In this section, we delve into how the first windshield wipers worked and the challenges faced by early automobile manufacturers.

In the early days of automotive design, driver visibility was a significant concern, especially during inclement weather. The first windshield wipers were manually operated devices that required the driver to intervene directly. This section explores their mechanics and the difficulties faced by early manufacturers in ensuring safety and visibility.

The initial designs of windshield wipers were quite simple, often consisting of a metal arm and a rubber blade. Drivers had to manually move the arm back and forth across the windshield to clear rain or debris. This method proved to be labor-intensive and often ineffective, particularly in heavy rain. The lack of automation meant that drivers had to divert their attention from the road, which posed additional safety risks.

- Mechanical Operation: The early wipers were operated using a lever or crank system, which required physical effort from the driver.

- Visibility Challenges: During severe weather, the limited effectiveness of these manual systems highlighted the urgent need for better solutions.

- Design Limitations: The fixed position of the wiper arms meant that they could not cover the entire windshield effectively, leaving blind spots.

As vehicles became more popular, the demand for improved visibility led to innovations in wiper design. One of the major challenges was to create a system that could operate effectively without compromising the driver’s focus on the road. This need drove inventors to experiment with various mechanisms, leading to significant advancements.

By the 1920s, the introduction of electric windshield wipers marked a pivotal shift in wiper technology. Electric wipers allowed for automatic operation, drastically improving driver visibility. The switch from manual to electric systems not only enhanced convenience but also significantly improved safety, as drivers could maintain their focus on the road while the wipers worked automatically.

These electric systems utilized a motor to control the movement of the wipers, enabling them to operate at varying speeds depending on the intensity of the rain. This innovation represented a major leap forward in automotive technology, as it addressed many of the limitations associated with manual wipers.

In conclusion, the evolution of windshield wipers from manual to electric systems reflects the broader advancements in automotive safety and technology. Early designs faced numerous challenges, but the drive for improved visibility led to innovations that have become standard in modern vehicles. Understanding this history not only highlights the importance of windshield wipers but also underscores the ongoing quest for safety in automotive design.

Manual vs. Automatic Wipers

The evolution of windshield wipers has been a remarkable journey, reflecting the continuous advancements in automotive technology. One of the most significant milestones in this evolution is the transition from manual to automatic windshield wipers. This shift not only brought about enhanced convenience for drivers but also played a crucial role in improving overall driving safety.

Manual windshield wipers were the earliest form of wiper technology, requiring direct driver intervention to operate. Typically, these wipers were controlled by a lever or a crank, which the driver would need to manipulate to clear rain or debris from the windshield. While these systems were innovative for their time, they posed several challenges, particularly during heavy rainfall.

- Driver Distraction: Constantly adjusting the wipers could distract drivers from the road, increasing the risk of accidents.

- Inconsistent Performance: The effectiveness of manual wipers depended on the driver’s reaction time and ability to operate them smoothly.

- Limited Visibility: In adverse weather conditions, manual wipers often struggled to keep up with the amount of water on the windshield, compromising visibility.

The introduction of automatic windshield wipers in the 1920s marked a turning point in automotive design. These systems utilized electric motors to operate the wipers, allowing for a more consistent and reliable performance. Drivers no longer needed to worry about manually adjusting the wipers, which significantly enhanced their focus on the road.

- Enhanced Safety: Automatic wipers respond to changing weather conditions, ensuring optimal visibility at all times.

- Convenience: Drivers can concentrate on navigating the road without the distraction of manually operating the wipers.

- Improved Design: Modern automatic wipers are often equipped with sensors that detect rain, adjusting their speed and frequency accordingly.

As technology has advanced, so have windshield wiper systems. Innovations such as rain sensors, which automatically activate the wipers when moisture is detected, have become standard in many vehicles. Additionally, advancements in wiper blade materials have improved durability and performance, allowing for better contact with the windshield surface.

Looking ahead, the future of windshield wipers appears promising. With the integration of smart technology, we may see further enhancements that improve functionality and safety. For instance, wipers could potentially be linked to vehicle systems that monitor weather conditions, providing real-time adjustments to wiper speed and operation.

In conclusion, the evolution from manual to automatic windshield wipers signifies a major leap in automotive safety and convenience. As technology continues to advance, we can expect even greater innovations that will further enhance the driving experience.

Early Manual Wiper Designs

The inception of windshield wipers can be traced back to a time when automobiles were still a novelty. Initial designs featured a simple arm and blade mechanism that required the driver to operate them manually. This rudimentary approach proved to be a challenge, especially during adverse weather conditions such as heavy rain and snow. The manual operation of these wipers necessitated the driver’s constant attention, diverting focus from the road and increasing the risk of accidents. The need for improved designs became evident as more vehicles hit the roads.

In the early 1900s, vehicles were primarily designed for functionality, and the concept of driver convenience was still in its infancy. The first windshield wipers were often operated using a lever or a crank, which meant that the driver had to physically move the wipers back and forth across the windshield. This process was not only cumbersome but also limited the effectiveness of the wipers, particularly when faced with heavy precipitation. As a result, visibility was often compromised, leading to dangerous driving conditions.

Moreover, the manual wipers had a significant drawback: they could not be adjusted for different weather conditions. For instance, during a torrential downpour, the driver would struggle to maintain visibility, as the wipers could only move at a fixed speed determined by the driver’s own effort. This highlighted a critical gap in the automotive design of the time, where safety and convenience were not yet fully prioritized.

As the automotive industry began to recognize the importance of driver safety, the limitations of these early manual wiper designs became a catalyst for innovation. Engineers and inventors started to explore ways to automate the wiper system, leading to the development of more advanced mechanisms. The transition from manual to automatic wipers marked a significant turning point in the evolution of windshield technology.

In summary, while early manual wiper designs were a necessary step in the history of automotive safety, they underscored the need for innovation. The limitations faced by drivers during inclement weather paved the way for the introduction of electric wipers in the 1920s, which would eventually revolutionize the industry. The journey from manual to automatic wipers illustrates the ongoing quest for enhanced safety and convenience in vehicle design.

Introduction of Electric Wipers

The introduction of electric windshield wipers in the 1920s marked a pivotal moment in automotive history. This innovation not only transformed the way drivers interacted with their vehicles during inclement weather but also significantly enhanced road safety and visibility. The transition from manual to electric systems represented a leap forward, making driving in rain, snow, and fog much safer and more convenient.

Before the advent of electric wipers, drivers relied on manual windshield wipers. These early designs required physical effort to operate, often distracting the driver from the road. The mechanics involved a simple arm and blade system, which was not only tedious but also inefficient during heavy precipitation. As a result, visibility was frequently compromised, leading to increased risk on the roads.

The shift to electric windshield wipers revolutionized the driving experience. With the introduction of this technology, wipers could operate automatically, responding to the intensity of the rain. This meant that drivers could focus more on the road, enhancing overall safety. The electric wipers were equipped with a motor that allowed for variable speeds, adjusting to the weather conditions, which was a significant improvement over their manual predecessors.

- Automatic Operation: Electric wipers could be activated with the push of a button, eliminating the need for manual effort.

- Variable Speed Settings: Drivers could choose different speeds depending on the severity of the weather, offering greater control.

- Improved Blade Design: The introduction of flexible wiper blades ensured better contact with the windshield, enhancing water removal efficiency.

The introduction of electric wipers not only improved functionality but also influenced the overall design of vehicles. Manufacturers began to prioritize driver comfort and safety features, integrating electric wipers into the standard equipment of new models. This shift reflected a broader trend in the automotive industry towards greater innovation and user-friendliness.

Since the 1920s, windshield wiper technology has continued to evolve. Modern advancements include features such as rain-sensing technology, which automatically activates the wipers when moisture is detected on the windshield. Additionally, innovations like heated wiper blades and aerodynamic designs have further enhanced their performance, ensuring that they remain effective in even the harshest weather conditions.

The introduction of electric windshield wipers in the 1920s was a groundbreaking advancement that transformed automotive safety and convenience. By eliminating the need for manual operation and enhancing visibility during adverse weather, electric wipers have become an essential component of modern vehicles. As technology continues to advance, we can expect further improvements that will enhance the driving experience even more.

Innovations in Wiper Technology

Over the decades, windshield wiper technology has continued to evolve, incorporating various innovations that enhance performance and reliability. This section delves into key technological advancements that have shaped modern wipers.

Windshield wipers have undergone significant transformations since their inception. Modern advancements have not only improved the efficiency of wipers but also increased their durability and adaptability to various weather conditions. Here are some notable innovations:

- Variable Speed Wipers: Early wipers operated at a single speed, which was often insufficient during changing weather conditions. The introduction of variable speed settings allows drivers to adjust the speed of the wipers based on the intensity of the rain, enhancing visibility and safety.

- Rain Sensors: The integration of rain sensors has revolutionized wiper operation. These sensors detect moisture on the windshield and automatically activate the wipers at the appropriate speed. This hands-free technology not only improves convenience but also ensures optimal visibility without driver intervention.

- Heated Wipers: In colder climates, ice and snow can obstruct visibility. Heated wipers are designed to prevent ice accumulation on the blade, ensuring they remain functional even in extreme weather. This innovation is crucial for maintaining safety during winter months.

- Advanced Blade Materials: The materials used in wiper blades have evolved significantly. Modern blades often feature composite materials that enhance flexibility and durability, ensuring a more effective wipe and longer lifespan.

- Windshield Wiper Aerodynamics: The design of wiper arms and blades has also seen innovation. Aerodynamic designs help reduce lift and improve contact with the windshield, resulting in a cleaner wipe and reduced noise during operation.

Each of these innovations contributes to the overall performance of windshield wipers. For instance, variable speed wipers allow for a customized response to rain intensity, which is vital for maintaining driver focus and safety. Additionally, rain sensors eliminate the need for manual adjustments, allowing drivers to concentrate on the road.

Furthermore, heated wipers address the challenges posed by icy conditions, ensuring that drivers have a clear view regardless of the weather. The advancements in blade materials and aerodynamics not only improve the wiping action but also reduce wear and tear, leading to more reliable performance over time.

The future of windshield wiper technology looks promising, with ongoing research and development aimed at further enhancing safety and convenience. Potential innovations may include:

- Smart Wipers: Integrating wipers with vehicle systems could allow for predictive adjustments based on weather forecasts or real-time data.

- Self-Cleaning Wipers: Future designs may incorporate self-cleaning technologies to ensure optimal performance without the need for manual maintenance.

- Eco-Friendly Materials: As sustainability becomes increasingly important, the use of biodegradable or recyclable materials in wiper production could become a standard.

In conclusion, the evolution of windshield wiper technology reflects a broader trend in automotive innovation, prioritizing safety, convenience, and efficiency. As these advancements continue to emerge, drivers can expect enhanced visibility and improved safety on the roads.

Who Were the Pioneers Behind Windshield Wipers?

The development of windshield wipers is a fascinating journey marked by the ingenuity of several inventors whose contributions have shaped the automotive industry. Understanding the pivotal roles these pioneers played not only highlights their individual accomplishments but also underscores the collaborative nature of innovation in technology.

Windshield wipers have become an essential feature in modern vehicles, ensuring driver safety and visibility during adverse weather conditions. The evolution of this critical component can be attributed to a series of innovative minds. Below, we explore the key figures who made significant strides in the design and functionality of windshield wipers.

Mary Anderson is often recognized as the pioneer of the first functional windshield wiper, patented in 1903. Her design involved a lever mechanism that allowed the driver to manually operate a blade across the windshield. Although her invention did not gain commercial success at the time, it set the groundwork for future advancements in wiper technology.

Anderson’s invention sparked interest among automotive manufacturers, leading to further refinements. The concept of a mechanical wiper system became a point of focus for many inventors, paving the way for more sophisticated designs. Her efforts highlighted the necessity for improved visibility, especially in challenging weather conditions.

- Charles H. H. M. H. R. G. D. K. E. R. B. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F.

- John W. H. L. S. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F.

- Robert H. S. H. E. F. W. H. E. P. R. T. E. N. R. M. P. T. E. S. W. H. E. F.

The collective advancements made by these inventors led to the development of automatic windshield wipers, which are now standard in vehicles worldwide. This transition not only improved driver convenience but also significantly enhanced safety on the roads. The integration of sensors and variable speed controls in modern wipers is a direct result of the foundational work laid by these pioneers.

In summary, the evolution of windshield wipers is a testament to the creativity and determination of several inventors. Their contributions have made driving safer and more comfortable, showcasing the importance of innovation in automotive technology.

Mary Anderson’s Contribution

to the invention of windshield wipers is a captivating chapter in automotive history. In 1903, she designed the first functional windshield wiper, a revolutionary concept that would eventually change how drivers experienced visibility during inclement weather. Although her invention did not achieve commercial success at the time, it was a crucial stepping stone that paved the way for future advancements in wiper technology.

Anderson’s design was innovative for its time. It featured a simple yet effective mechanism that consisted of a lever inside the vehicle, which allowed the driver to manually operate a blade that wiped the windshield clean. This was a significant improvement over the existing solutions, which often involved the driver having to stop and manually clean the glass, thereby compromising safety and convenience. The ability to maintain a clear view of the road while driving in rain or snow was a major leap forward in automotive design.

Despite its potential, Anderson’s invention faced several challenges. The automotive industry was still in its infancy, and many manufacturers were hesitant to adopt new technologies. Moreover, the concept of windshield wipers was met with skepticism, as the prevailing mindset favored more traditional means of vehicle operation. This reluctance contributed to the initial lack of commercial success for her design.

However, Anderson’s contribution did not go unnoticed. Over the years, her design inspired other inventors to refine and enhance the concept. The introduction of electric windshield wipers in the 1920s marked a significant evolution in wiper technology. These electric systems eliminated the need for manual operation, allowing for automatic function and greatly improving driver visibility during adverse weather conditions.

In addition to Anderson, several other inventors played a pivotal role in advancing windshield wiper technology. For instance, William M. Smith patented the first electric wiper in 1921, which showcased the practicality and efficiency of automated systems. This collaboration among various inventors and engineers ultimately led to the sophisticated windshield wipers we rely on today.

The impact of Mary Anderson’s initial design is profound. Modern windshield wipers are equipped with various features, including adjustable speeds, rain sensors, and even heated blades, all of which enhance driver safety and comfort. These advancements are a testament to the foundational work laid by Anderson and her contemporaries.

In conclusion, while Mary Anderson may not have reaped the financial rewards of her invention, her legacy endures in the automotive industry. Her pioneering spirit and innovative thinking laid the groundwork for a safety feature that is now standard in all vehicles. The evolution of windshield wipers reflects a broader narrative of technological progress, demonstrating how one woman’s vision can lead to significant advancements in vehicle safety and functionality.

The Role of Other Inventors

Windshield wipers are an essential component of modern vehicles, ensuring clear visibility during adverse weather conditions. While Mary Anderson is often credited with inventing the first functional windshield wiper in 1903, her contribution was just the beginning of a long journey of innovation in wiper technology.

Following Anderson’s pioneering design, several other inventors played crucial roles in refining and enhancing windshield wiper technology. Their collective efforts have led to the sophisticated automatic systems we depend on today, significantly improving automotive safety.

Throughout the 20th century, numerous inventors and engineers recognized the limitations of early wipers. They sought to address challenges such as inconsistent operation and the need for manual intervention. This section highlights key figures and their contributions:

- William M. McKinley: In the 1920s, McKinley introduced the first electric windshield wiper system. This innovation allowed wipers to operate automatically, responding to the driver’s needs without manual effort.

- John W. McCulloch: McCulloch’s design improvements in the 1930s included the development of a two-speed wiper motor, providing drivers with greater control over wiper speed and efficiency.

- Robert Kearns: In the 1960s, Kearns invented the intermittent windshield wiper system, which allowed wipers to pause between sweeps. This feature not only conserved energy but also enhanced driver visibility during light rain.

The advancements made by these inventors were instrumental in transforming windshield wipers from a basic tool into a critical safety feature in vehicles. With the introduction of electric and intermittent wipers, drivers no longer had to struggle with manual operation during harsh weather conditions. This evolution has led to:

- Improved Visibility: Automatic systems ensure that the windshield remains clear, allowing drivers to maintain focus on the road.

- Increased Driver Comfort: The convenience of automatic wipers reduces distractions, enabling drivers to concentrate on their driving tasks.

- Enhanced Safety: With better visibility, the risk of accidents during rain or snow is significantly reduced, contributing to overall road safety.

Today, windshield wiper technology continues to evolve with advancements in materials and electronics. Innovations such as rain-sensing wipers, which automatically adjust their speed based on the intensity of rainfall, are becoming increasingly common in new vehicles. These developments showcase the ongoing commitment to enhancing driver safety and comfort.

In conclusion, the journey of windshield wiper technology is a testament to the collaborative efforts of various inventors who have shaped its evolution. From manual systems to sophisticated automatic designs, each advancement has played a vital role in ensuring safety and convenience for drivers everywhere.

Frequently Asked Questions

- Who invented the first windshield wiper?

The first functional windshield wiper was invented by Mary Anderson in 1903. Although her design wasn’t commercially successful at the time, it paved the way for future innovations in automotive safety.

- How did early windshield wipers operate?

Early windshield wipers were manually operated, requiring the driver to intervene to clear the windshield. This posed challenges, especially during heavy rain, making visibility a significant concern for drivers.

- What advancements have been made in windshield wiper technology?

Over the years, windshield wiper technology has evolved significantly. The introduction of electric wipers in the 1920s marked a major turning point, allowing for automatic operation and greatly enhancing driver visibility in adverse weather.

- Why are automatic windshield wipers important?

Automatic windshield wipers improve convenience and safety. They adjust their speed based on the intensity of the rain, ensuring that drivers maintain optimal visibility without manual effort, which is crucial for safe driving.

- Who else contributed to the development of windshield wipers?

Besides Mary Anderson, several other inventors played key roles in refining windshield wiper technology, leading to the efficient automatic systems we use today. Their collective efforts have significantly enhanced automotive safety.